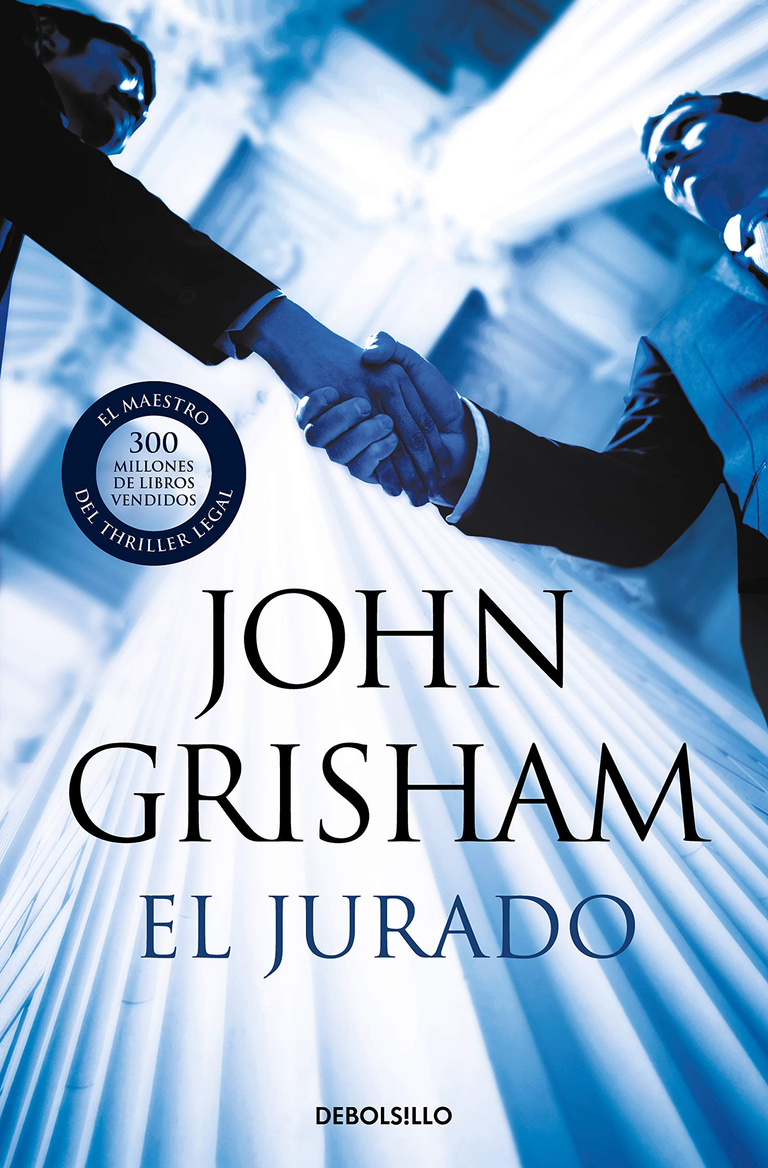

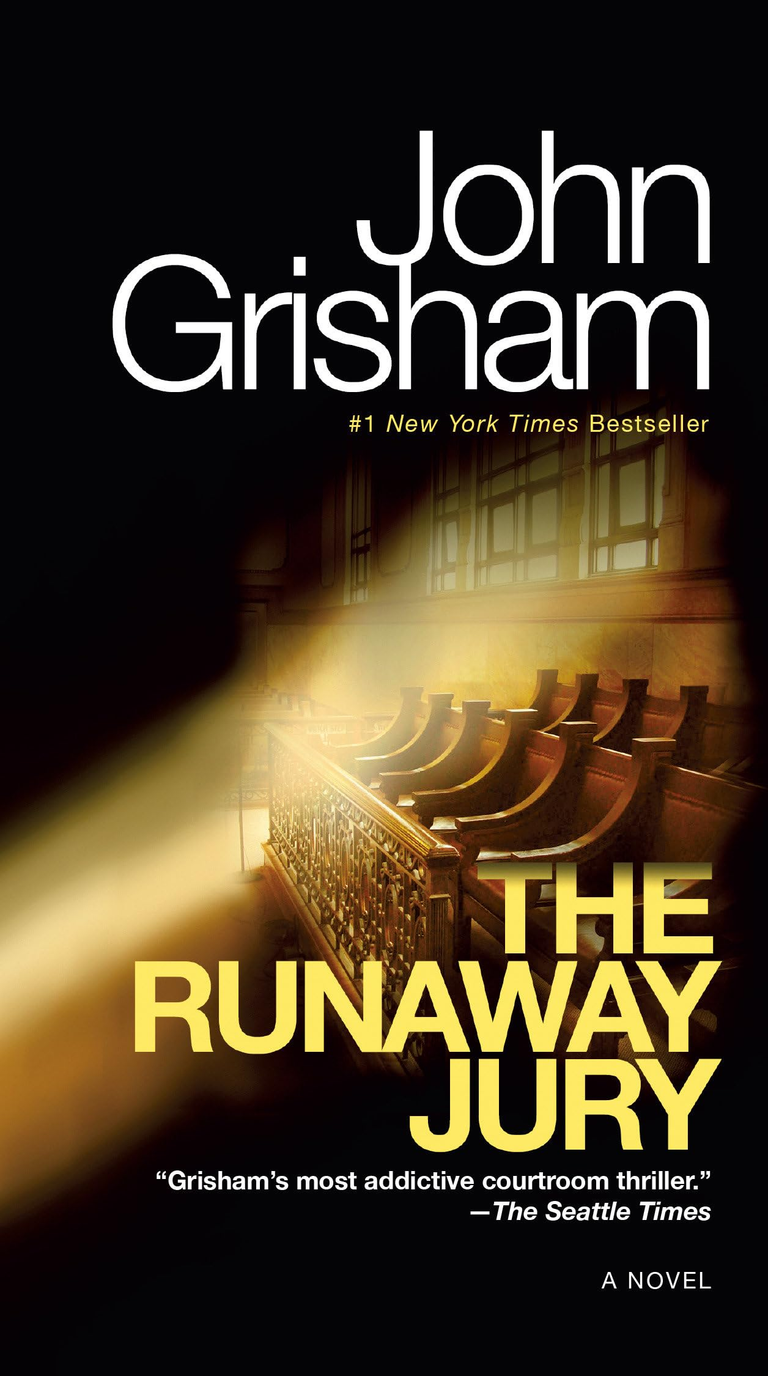

El Jurado de John Grisham reproduce la constante lucha de todas aquellas personas comunes contra los grandes intereses económicos.

El Jurado es una novela de suspenso legal del escritor estadounidense John Grisham. Publicada en 1996, es la séptima novela del autor.

La adaptación cinematográfica del mismo nombre se estrenó en 2003, protagonizada por Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, John Cusack y Rachel Weisz.

John Grisham's The Runaway Jury portrays the constant struggle of ordinary people against big business interests.

The Jury is a legal thriller by American writer John Grisham. Published in 1996, it is the author's seventh novel.

The film adaptation of the same name was released in 2003, starring Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, John Cusack, and Rachel Weisz.

Personajes principales / Main Characters

- Nicolás Pascual: Jurado. También conocido como Perry Hirsch y como Jeff Kerr

- Marlee: compañera y cómplice de Nicholas. También conocida como Claire Clement y como Gabrielle Brant

- Rankin Fitch: abogado defensor, trabaja en las sombras para ayudar a sus clientes a ganar el juicio

- Frederick Harkin: Juez de primera instancia

- Nicolás Pascual: Jury member. Also known as Perry Hirsch and Jeff Kerr.

- Marlee: Nicholas's partner and accomplice. Also known as Claire Clement and Gabrielle Brant

- Rankin Fitch: Defense attorney, working in the shadows to help his clients win their cases

- Frederick Harkin: Trial Judge

Personajes secundarios / Supporting Characters

- Wendhall Rohr: abogado principal de la acusación

Cable de Durwood: Abogado principal de la defensa - Herman Grimes: Jurado y portavoz del jurado (posteriormente reemplazado)

- Millie Dupree: miembro del jurado

- Lonnie Shaver: miembro del jurado

- Jerry Fernández: Jurado

- Sylvia "Fuffy" Taylor-Tatum: miembro del jurado

- Rikki Coleman: miembro del jurado

- Gladys Card: jurada

- Stella Hulic: miembro del jurado (posteriormente reemplazada)

- Frank "Coronel" Herrera: jurado (posteriormente reemplazado)

- Angel Weese: miembro del jurado

- Loreen Duke: miembro del jurado

- Philip Savelle: Jurado de reserva n.º 1

- Henry Vu: Jurado de reserva n.º 2

- Shine Royce: Jurado de reserva n.º 3

- Wendhall Rohr: Lead Prosecuting Attorney

Durwood Cable: Lead Defense Attorney- Herman Grimes: Juror and Foreperson (later replaced)

- Millie Dupree: Juror

- Lonnie Shaver: Juror

- Jerry Fernandez: Juror

- Sylvia "Fuffy" Taylor-Tatum: Juror

- Rikki Coleman: Juror

- Gladys Card: Juror

- Stella Hulic: Juror (later replaced)

- Frank "Colonel" Herrera: Juror (later replaced)

- Angel Weese: Juror

- Loreen Duke: Juror

- Philip Savelle: Reserve Juror #1

- Henry Vu: Reserve Jury No. 2

- Shine Royce: Reserve Jury No. 3

Un grupo de importantes abogados acusa de homicidio a las grandes productoras de cigarrillos a raíz de la muerte de un fumador.

La industria tabacalera se tambalea: saben que una sola sentencia en su contra provocaría una avalancha de demandas de indemnización que los llevaría a la ruina. Pero a los grandes magnates todo esto no les preocupa. En 1989, Grisham se inició en el mundo literario con la obra Tiempo de matar pero fue con su segunda novela, La tapadera, con la que alcanzó la popularidad.

Desde entonces, la aparición de todas sus obras siguientes tales como: El informe Pelicano, El cliente, El jurado, Causa justa entre otras, han sido recibidas con enorme entusiamo, no sólo por parte de los lectores y críticos, sino también por la industria cinematográfica, que las ha convertido en auténticas superproducciones cinematográficas.

A group of prominent lawyers is accusing major cigarette manufacturers of manslaughter following the death of a smoker.

The tobacco industry is reeling: they know that a single ruling against them would trigger an avalanche of compensation claims that would lead to their ruin. But all this doesn't worry the bigwigs. In 1989, Grisham made her literary debut with A Time to Kill, but it was with her second novel, The Firm, that she achieved popularity.

Since then, the release of all her subsequent works, such as The Pelican Brief, The Client, The Jury, Just Cause, and others, have been received with enormous enthusiasm, not only by readers and critics, but also by the film industry, which has turned them into true blockbusters.

La mitad de la cara de Nicholas Easter estaba cubierta por los teléfonos móviles que llenaban el escaparate de una tienda. Sus ojos no miraban hacia la cámara oculta, sino que se desviaban ligeramente hacia la izquierda, tal vez hacia un cliente o hacia el grupo de chicos reunidos frente al mostrador donde se exponían los últimos juegos electrónicos de fabricación asiática. Tomada a cuarenta metros de distancia por un hombre obstaculizado por el intenso ir y venir de visitantes y compradores, la foto era sin embargo nítida y mostraba un rostro joven y apuesto de rasgos marcados. Pascua tenía veintisiete años, según la información que ya obraba en su poder. Sin gafas. Ni pendiente en la nariz ni corte de pelo extraño. Nada que indicara que pertenecía a la cohorte habitual de jóvenes dependientes de tiendas de informática que cobran cinco dólares la hora. Según el cuestionario, llevaba allí cuatro meses. También afirmaba ser estudiante-trabajador, pero en trescientas millas a la redonda no se había encontrado ninguna matrícula universitaria. Al menos en eso mentía, estaban seguros.

No podía ser de otro modo. Su información era demasiado precisa. Si hubiera sido estudiante, habrían sabido dónde, durante cuánto tiempo, en qué disciplina, con qué rendimiento. Sin duda lo habrían sabido. Era empleado en el departamento de informática de un centro comercial. Ni más ni menos. Tal vez había tenido la intención de matricularse en alguna escuela. Tal vez lo había dejado sin renunciar al placer de calificarse como estudiante. Quizá se sentía mejor así, le daba cierto tono.

Pero ahora no estaba matriculado en ningún curso, ni lo había estado en el pasado reciente. Entonces, ¿se podía confiar en él? La pregunta ya había sido tema de debate dos veces, cuando su nombre había sido seleccionado de la lista y su cara había aparecido en la pantalla. Habían llegado a la conclusión de que era una mentira inofensiva.

No fumaba. En el centro comercial la prohibición se cumplía a rajatabla, pero le habían visto (no fotografiado) tomando un taco en el Food Garden con un colega que, mientras bebía una limonada, se había fumado dos cigarrillos. Evidentemente, a Easter no le molestaba el tabaco. Al menos no era un fanático.

En la foto aparecía delgado de cara, bronceado, con un atisbo de sonrisa en los labios cerrados. Bajo la chaqueta roja del uniforme llevaba una camisa blanca sin botones en el cuello y una elegante corbata de rayas. Su aspecto era esbelto, en buena forma física. Quienquiera que hubiera tomado la foto también había entrevistado a Nicholas fingiendo buscar un artículo de producción: dijo que hablaba con propiedad, era servicial, competente, básicamente simpático. Según la placa que llevaba en la solapa, era capataz, pero también se había identificado a otros dos empleados con la misma cualificación.

Al día siguiente, una atractiva chica en vaqueros que deambulaba por el departamento de software se encendió un cigarrillo. Por casualidad, Nicholas Easter era el vendedor más cercano, o lo que fuera. Se acercó a ella y le pidió que lo apagara. La chica fingió estar molesta, incluso ofendida, e intentó provocarle. Easter mantuvo una actitud educada, explicándole que la prohibición no admitía excepciones. La invitó a fumar en otro sitio. ¿Le molesta el humo?», le preguntó dando una calada. No», respondió Easter. Pero molesta al dueño del centro comercial». Volvió a pedirle que dejara de fumar. Ella replicó que estaba allí para comprar una nueva radio digital y le preguntó si podía conseguirle un cenicero. Nicholas cogió una lata vacía de debajo del mostrador y le arrancó el cigarrillo de los dedos, apagándolo en la lata. Durante veinte minutos hablaron de varios modelos de radios mientras ella seguía indecisa sobre la elección, provocando abiertamente el interés de él. Una vez pagada la radio, le dejó su número de teléfono. Easter prometió llamarla alguna vez.

El episodio duró veinticuatro minutos y fue grabado por un pequeño aparato que la chica llevaba en el bolso. La cinta fue escuchada por los abogados y sus peritos mientras se proyectaba la fotografía en la pared. El informe escrito de la chica llenaba seis páginas del expediente de Easter y contenía sus observaciones: desde sus zapatos (unas Nike viejas) hasta su aliento (chicle de canela), pasando por su vocabulario (nivel universitario) y la forma en que había cogido y manipulado su cigarrillo. En su experta opinión, Easter nunca había fumado.

Escucharon el tono agradable de su voz, la profesionalidad de los argumentos con los que presentaba sus productos, la simpatía entrañable de sus galanterías, y sacaron un veredicto positivo. Era inteligente y no tenía prejuicios contra el tabaco. No se ajustaba a su modelo de jurado, pero sin duda era algo a tener en cuenta. El problema con Easter, el jurado potencial número cincuenta y seis, era que sabían muy poco de él. Hacía menos de un año que había aparecido en la Costa del Golfo y no se sabía de dónde había salido. Su pasado era un misterio. Vivía en un miniapartamento alquilado a ocho manzanas del juzgado (tenían fotografías del edificio) y había empezado trabajando de camarero en una casa de juego frente al mar. Había ascendido rápidamente al rango de crupier en la mesa de blackjack, pero dejó el puesto dos meses después.

Cuando Mississippi legalizó el juego, una docena de casinos surgieron de la noche a la mañana a lo largo de la costa, dando paso a una nueva ola de prosperidad. La gente había venido de todas partes en busca de trabajo, así que era lógico suponer que Nicholas Easter se había trasladado a Biloxi por la misma razón que había llevado allí a otros diez mil como él. Lo único que le distinguía era que se había inscrito tan rápidamente en el censo electoral.

Era propietario de un Volkswagen Escarabajo de 1969, cuya foto se proyectaba en la pared en sustitución de la de su rostro. No es de extrañar: veintisiete años, soltero, autodenominado adicto al trabajo, era estadísticamente el típico propietario de un vehículo así. No había pegatinas que indicaran simpatías políticas, conciencia cívica o pasiones deportivas. Ninguna marca de coche universitario. Ni siquiera una desvaída indicación del concesionario del que procedía el vehículo. Para el espectador, el Escarabajo no tenía más significado que un nivel de vida que rozaba la pobreza.

El encargado del proyector y de la mayor parte de la exposición verbal era Carl Nussman, un abogado de Chicago que había dejado de ejercer y ahora dirigía su propia consultora de jurados. A cambio de una pequeña cantidad de dinero, Carl Nussman y su equipo garantizaban la selección del mejor jurado. Recogían datos, conseguían fotografías, grababan voces, enviaban rubias en vaqueros ajustados para crear las situaciones adecuadas. Carl y su organización operaban al límite de la ley y la ética profesional, pero habría sido imposible involucrarles en nada ilícito. Al fin y al cabo, no hay nada ilegal ni inmoral en fotografiar a ciudadanos para ser seleccionados para un jurado. Ya seis meses antes, luego dos más y una última vez hace un mes, habían llevado a cabo intensas encuestas telefónicas en el condado de Harrison para calibrar las actitudes generales en cuestiones relacionadas con el tabaco y construir la plantilla del jurado perfecto. No se había pasado por alto ninguna vía o atajo; no había ningún lado oscuro que no hubieran investigado. Al final habían elaborado un dossier para cada uno de los posibles jurados.

Carl pulsó un botón y el Volkswagen fue sustituido por la imagen anónima de la fachada de un edificio desollado, aquel en el que vivía Nicholas Easter. Otro cambio de diapositiva y volvió a aparecer su rostro.

Así que sólo tenemos tres fotos del número cincuenta y seis», concluyó Carl con una nota de decepción, lanzando una mirada de reproche al fotógrafo, uno de sus muchos investigadores privados, que ya le había explicado que no podía fotografiar al joven sin arriesgarse a ser descubierto. El fotógrafo estaba sentado contra la pared, frente a la larga mesa alrededor de la cual se habían sentado los abogados, los asistentes y los expertos del jurado. Su paciencia estaba ya al límite. Eran las siete de la tarde de un viernes, en la pared estaba el número cincuenta y seis y aún faltaban ciento cuarenta. Iba a ser un fin de semana horrible. Necesitaba una copa.

Cinco o seis abogados con camisas arrugadas y mangas remangadas tomaban notas sin cesar, levantando de vez en cuando la vista hacia el retrato de Nicholas Easter, allá, detrás de Carl. El variopinto grupo de expertos (psiquiatra, sociólogo, grafólogo, profesor de Derecho, etc.) hojeaba archivos e impresiones. No sabían qué pensar de Easter. Era un mentiroso y ocultaba algo de su pasado, pero el candidato que tenían sobre el papel y en la pared parecía digno.

Quizá no mentía. Tal vez había asistido a alguna escuela de segunda categoría en Arizona el año anterior y no habían podido localizarlo.

Denle una oportunidad de redimirse, pensó el fotógrafo, pero mantuvo la boca cerrada. En aquella sala de cabezas huecas con trajes de sastre, su opinión sería tenida en la más baja consideración. No le correspondía expresarla.

Carl se aclaró la garganta mientras echaba un último vistazo y anunciaba el número cincuenta y siete. El rostro sudoroso de una joven madre apareció en la pared y al menos dos de los presentes soltaron una risita. Traci Wilkes», la presentó Carl, como si fuera una vieja amiga. Se oyó un leve crujido de papeles sobre la mesa. Treinta y tres años, casada, madre de dos hijos, esposa de médico, dos clubes de campo, dos clubes de salud, una lista interminable de afiliaciones a otros clubes». Carl recitó los datos de memoria mientras manejaba el proyector. La cara sonrojada de Traci desapareció y su lugar lo ocupó otra foto de cuerpo entero, en la que se la veía trotando por una acera con un chillón traje elástico rosa y negro, unas Reebok inmaculadas, visera blanca, el último modelo de gafas de sol con cristales reflectantes y el pelo largo recogido en una perfecta coleta. Empujaba el cochecito de un bebé. Traci vivía para sudar. Estaba bronceada y en buena forma, pero no tan delgada como cabría esperar. Tenía algunos malos hábitos. Otra imagen de Traci en su Mercedes familiar negro con niños y perros mirando por todas las ventanas. Otra de Traci cargando bolsas de la compra en el mismo vehículo, Traci con otro par de zapatillas deportivas, pantalones cortos ajustados y el aspecto de alguien que siempre intenta parecer atlético. Había sido fácil seguirla porque iba a un ritmo frenético y no se había detenido ni un momento a mirar a su alrededor.

Carl se desplazó por las fotos de la casa de los Wilkes, una imponente vivienda unifamiliar de tres plantas que era la tarjeta de visita de un médico. Se entretuvo un rato, queriendo dedicar más tiempo a la última imagen. Luego proyectó a Traci, de nuevo brillante por el sudor, con su característica bicicleta abandonada en la hierba. Estaba sentada bajo un árbol del parque, lejos de todo el mundo, medio escondida... ¡fumando un cigarrillo!

El fotógrafo se burló. Era su pequeña obra maestra, aquella imagen robada a cien metros de distancia, que retrataba a la mujer de un médico fumando un cigarrillo a escondidas. Él no sabía que era fumadora. Se había detenido casualmente a fumar un cigarrillo cerca de un pequeño puente cuando ella pasó a su lado. Había permanecido en el parque durante media hora hasta que la vio detenerse y rebuscar en la bolsa de su bicicleta.

Half of Nicholas Easter's face was covered by the mobile phones filling a shop window. His eyes were not looking towards the hidden camera and were instead turned slightly to the left, perhaps on a customer or perhaps on the group of boys gathered in front of the counter where the latest Asian-made electronic games were on display. Taken at a distance of forty metres by a man obstructed by the intense coming and going of visitors and shoppers, the photo was nevertheless sharp and showed a handsome young face with marked features. Easter was twenty-seven years old, according to information already in their possession. No eyeglasses. No nose ring or bizarre haircut. Nothing to indicate that he belonged to the usual cohort of young computer shop assistants at five dollars an hour. According to the questionnaire, he had been there for four months. He also claimed to be a student-worker, but within three hundred miles no college enrolment had been found. At least he was lying about that, they were certain.

It could not be otherwise. Their information was too precise. If he had been a student, they would have known where, for how long, in what discipline, with what performance. They would certainly have known. He was a clerk in the computer department of a shopping centre. Nothing more or less. Perhaps he had intended to enrol in some school. Maybe he had quit without giving up the pleasure of qualifying as a student. Maybe he felt better that way, he felt it gave him a certain tone.

But now he was not enrolled in any course, nor had he been in the recent past. So, could he be trusted? The question had been a topic of debate twice already, when his name had been selected from the list and his face had appeared on the screen. They had come to the conclusion that it was a harmless lie.

He did not smoke. At the mall the ban was strictly enforced, but he had been seen (not photographed) having a taco at the Food Garden with a colleague who, while drinking a lemonade, had smoked two cigarettes. Evidently Easter was not bothered by smoking. At least he was not a fanatic.

In the photo he appeared thin in the face, tanned, with a hint of a smile on his closed lips. Under his red uniform jacket he wore a white shirt without buttons at the collar and an elegant striped tie. He was trim in appearance, in good physical shape. Whoever had taken the photo had also interviewed Nicholas pretending to be looking for a production article: he said he spoke with propriety, was helpful, competent, basically nice. According to the badge he wore on his lapel he was a foreman, but two other employees with the same qualification had also been identified.

The next day an attractive girl in jeans wandering around the software department lit up a cigarette. By chance Nicholas Easter was the nearest salesman, or whatever he was. He approached her and asked her to put it out. The girl pretended to be annoyed, even offended, and tried to provoke him. Easter maintained a polite attitude, explaining to her that the ban did not allow for exceptions. He invited her to go and smoke elsewhere. ‘Does the smoke bother you?’ she had asked, taking a puff. ‘No,’ Easter had replied. ‘But it bothers the mall owner.’ He then asked her again to stop. She retorted that she was there to buy a new digital radio and asked him if he could get her an ashtray. Nicholas took an empty can from under the counter and pulled the cigarette from her fingers, putting it out in the can. For twenty minutes they discussed various models of radios while she continued to be undecided about the choice, teasing his interest with open provocation. Having paid for the radio, she left him her phone number. Easter promised to call her sometime.

The episode lasted twenty-four minutes and was recorded by a small device the girl had in her handbag. The tape was listened to by the lawyers and their experts while the photograph was projected on the wall. The girl's written report filled six pages of Easter's file and contained her observations: from her shoes (an old pair of Nike's) to her breath (cinnamon chewing gum), to her vocabulary (college level), to the way she had taken and handled her cigarette. In her expert opinion, Easter had never smoked.

They listened to the pleasant tone of his voice, the professionalism of the arguments with which he presented his products, the endearing friendliness of his pleasantries, and drew a positive verdict. He was intelligent and had no prejudice against tobacco. He did not adhere to their juror model, but he was certainly something to watch out for. The problem with Easter, potential juror number fifty-six, was that they knew so little about him. His appearance on the Gulf Coast was less than a year old and it was unknown where he had come from. His past was a mystery. He lived in a rented mini-apartment eight blocks from the courthouse (they had photographs of the building) and had started out working as a waiter in a waterfront gambling house. He had quickly risen to the rank of croupier at the blackjack table, but left the position two months later.

When Mississippi had legalised gambling, a dozen or so casinos had sprung up along the coast overnight, ushering in a new wave of prosperity. People had come from all over looking for work, so it was logical to assume that Nicholas Easter had moved to Biloxi for the same reason that had driven ten thousand others like him there. The only thing that distinguished him was that he had registered so quickly on the electoral roll.

He owned a 1969 Volkswagen Beetle, a photo of which was projected on the wall to replace the one of his face. No surprise: twenty-seven years old, a bachelor, self-styled workaholic, he was statistically the typical owner of such a vehicle. No stickers indicating political sympathies, civic awareness or sporting passions. No place-car markings at any university. Not even a faded indication of the dealer the vehicle came from. To the beholder, the Beetle had no meaning other than a standard of living that bordered on poverty.

Operating the projector and doing the bulk of the verbal exposition was Carl Nussman, a Chicago lawyer who had stopped practising and now ran his own jury consulting firm. In return for a small amount of money, Carl Nussman and his team guaranteed the selection of the best jury. They collected data, procured photographs, recorded voices, sent blondes in skinny jeans to create the right situations. Carl and his organisation were operating at the limits of the law and professional ethics, but it would have been impossible to entrap them in anything illicit. After all, there is nothing illegal or immoral about photographing citizens to be selected for a jury. Already six months earlier, then again two more and one last time a month ago, they had carried out intensive telephone surveys in Harrison County to gauge general attitudes on tobacco issues and construct the template for the perfect juror. No avenue or shortcut had been overlooked; there were no dark sides they had not investigated. In the end they had put together a dossier for each of the possible jurors.

Carl pressed a button and the Volkswagen was replaced by the anonymous image of a flayed building façade, the one in which Nicholas Easter lived. Another slide change and his face reappeared.

‘So we only have three pictures of number fifty-six,’ Carl concluded with a note of disappointment, casting a reproachful glance at the photographer, one of his many private investigators, who had already explained to him that he could not photograph the young man without risking detection. The photographer sat against the wall, facing the long table around which the lawyers, assistants and jury experts had taken their seats. He was already at the limits of his patience. It was seven o'clock on a Friday night, on the wall was the number fifty-six and there were still one hundred and forty to go. It was going to be a horrible weekend. He needed a drink.

Five or six lawyers in wrinkled shirts and rolled-up sleeves were incessantly taking notes, occasionally looking up at the portrait of Nicholas Easter, over there, behind Carl. The assorted group of experts (psychiatrist, sociologist, graphologist, law professor and so on) were flipping through files and printouts. They didn't know what to make of Easter. He was a liar and was hiding something from his past, yet the candidate they had on paper and on the wall seemed worthy.

Maybe he wasn't lying. Maybe he had attended some second-rate school in Arizona the previous year and they had been unable to track him down.

Give him a chance to redeem himself, the photographer thought, but kept his mouth shut. In that room of eggheads in tailoring suits his opinion would be held in the lowest regard. It was not his place to express it.

Carl cleared his throat as he took one last look and announced the number fifty-seven. The sweaty face of a young mother appeared on the wall and at least two of those present gave a giggle. ‘Traci Wilkes,’ Carl introduced her, as if she were an old friend. A faint rustling of papers on the table was heard. ‘Thirty-three years old, married, mother of two, wife of a doctor, two country clubs, two health clubs, an endless list of memberships to other clubs.’ Carl recited the data from memory as he operated the projector. Traci's flushed face disappeared and her place was taken by another full-length photo, in which she could be seen trotting along a pavement in a garish pink and black stretch suit, immaculate Reeboks, white visor, the latest model of sunglasses with reflective lenses, and long hair pulled back into a perfect ponytail. She was pushing an infant's pram. Traci lived to sweat. She was tanned and in great shape, but not exactly as slim as one would have expected. She had a few bad habits. Another image of Traci in her black family Mercedes with children and dogs looking out all the windows. Another of Traci loading shopping bags into the same vehicle, Traci with a different pair of sports shoes, tight shorts and the look of someone always trying to look athletic. It had been easy to tail her because she was moving at a frantic pace and hadn't stopped for a moment to look around.

Carl scrolled through photos of the Wilkes house, an imposing three-storey single-family house that was the calling card of a medical doctor. He lingered there for a while, wanting to devote more time to the last image. Then he projected Traci, again shiny with sweat, with her trademark bike abandoned in the grass. She was sitting under a tree in the park, away from everyone, half-hidden... smoking a cigarette!

The photographer sneered. It was his little masterpiece, that image stolen from a hundred metres away, depicting a doctor's wife sneaking a cigarette. He didn't know she was a smoker. He had casually stopped for a cigarette near a small bridge when she had darted past him. He had lingered in the park for half an hour until he saw her stop and rummage through her bike bag.

El autor da en el clavo con su objetivo de demostrar cómo un jurado puede decidir el resultado de un juicio y, al mismo tiempo, muestra lo fácil que es manipular al jurado y, por tanto, el resultado del juicio desde fuera.

¿Cómo se forma un jurado? ¿de quien? ¿Cómo se elabora un veredicto? A través de las aventuras del simpático Nicolás, descubriremos todo lo que ocurre detrás de un juicio y en la vida de los jurados. Temas que a primera vista pueden no parecer especialmente atractivos (¡yo mismo tuve esta sensación nada más coger el libro en cuestión!), pero que, gracias a la hábil pluma de Grisham, conseguirán captar vuestra atención en un crescendo de suspense y giros. Nada es lo que parece.

Muy recomendable.

The author hits the nail on the head in his aim to show how a jury can decide the outcome of a trial and, at the same time, shows how easy it is to manipulate the jury and thus the outcome of the trial from the outside.

How is a jury formed, by whom, and how is a verdict reached? Through the adventures of the friendly Nicolas, we will discover everything that goes on behind the scenes of a trial and in the life of the jurors. Subjects that at first glance may not seem particularly attractive (I myself had this feeling as soon as I picked up the book in question!), but which, thanks to Grisham's skilful pen, will manage to capture your attention in a crescendo of suspense and twists and turns. Nothing is as it seems.

Highly recommended.

Traducción efectuada con: / Translated with: DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Fuente imágenes / Source images: John Grisham Official Website.

El crédito por las imágenes de los divisores e imagen final va a YoPriceGallery. y a UnsplashLos he modificado usando el programa de distribución libre y gratuita Kolour Paint. / Credit for the images of the dividers and final image goes to YoPriceGallery and UnsplashI modified them using the freely distributed Kolour Paint.

| Blogs, Sitios Web y Redes Sociales / Blogs, Webs & Social Networks | Plataformas de Contenidos/ Contents Platforms |

|---|---|

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Un Libro de Cabecera. |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Rasetipi. |

| Red Social Twitter / Twitter Social Network | @hugorep |